Karma is a universal force that balances accounts. The need for such balancing crosses all cultures. In the West, we call it Justice and build courthouses, temples where accounts are balanced; where justice is dispensed. For a long rime I worked in those temples. Justice was not always found there, but Karma always comes to collect.

Several years ago, Broward sheriff deputies were patrolling a construction site around two AM. They saw a white pick-up truck leaving the site. When they stopped the truck, there were two men inside: Donald Mark Schoff and an individual Schoff claimed was his employee.

In the back of the truck, police found washing machines with the hoses cut. Schoff claimed that he had been asked to remove the appliances from the construction site. This was a lie. Police arrested Schoff. The next morning, the construction foreman reported that in several apartments they found appliances with the hoses cut that had been dragged at left near the doorway to each unit. By arresting him the night before, the police had interrupted Schoff, who planned to return to steal the remaining appliances.

Schoff claimed that his employee’s truck had broken down and that Schoff had merely come to the apartment complex to drive the man home. Inconsistencies in his story betrayed Schoff’s claim of innocence.

Schoff had no criminal record. Michael Satz was the State’s Attorney for Broward county and he offered Schoff a plea bargain. The offer was a withhold of adjudication and a period of probation. A “withhold” was a feature of Florida law in which a first-time offender was not adjudicated guilty if he completed a period of probation. In that way, an accused individual does not become a felon and retains all civil rights and privileges. Schoff refused the offer and found his way to me. That is how I came to represent him.

Immediately before trial, the State renewed its offer. Schoff’s motion to suppress evidence was denied. The police were in court and were ready to testify. Schoff’s mother urged him to take the offer because of the evidence against him. When I outlined the evidence for her, Schoff’s own mother said that if she was on the jury she would vote to convict her son.

Schoff’s case was then scheduled for trial and the Broward Circuit Court for the 17th Judicial Circuit accommodated him. Schoff did not testify. At the close of the State’s case, I moved for a directed verdict on the felony charges–there was no evidence offered concerning the value of the stolen property. The State only had to prove that the brand-new stolen washing machines were worth more than three hundred dollars, but as this was a felony case the value of the stolen goods was an element of the charge and could not be assumed. The State asked the circuit judge to take judicial notice of the value of a brand new washing machine, but that is not what judicial notice is for.

Schoff’s case went to the jury on misdemeanor theft charges. The Broward county jury found him guilty.

The judge immediately moved to sentencing. He told Schoff that the only reason why he wasn’t convicted of a felony was because of a technicality. The maximum sentence for a misdemeanor was one year minus one day. The judge sentenced Schoff to the full term, 364 days in the county jail.

Usually, a defendant under these circumstances will be remorseful–not so much regret for having committed the crime, but regret for not taking the plea offer. Had Schoff taken the plea offer, he could have avoided jail altogether.

County jail is not State prison. It is a place where individuals serve short sentences or wait for their cases to be tried. It houses all kind of offenders, from the most dangerous to the non-violent. While serving his time at the county jail, School met one of the most dangerous. Schoff complained to his new friend and cellmate how his trial was unfair and how he wanted revenge against the lawyer who had failed to win his case outright.

I went about my business. I was representing a pilot who had been named in a federal indictment along with Panamanian general Manuel Noriega. The prosecutor then was Richard Gregorie. Gregorie told me that if the government dismissed the case against General Noriega, as was then likely, that they would dismiss the case against my client too.

Negotiations between the Panamanian government and the United States broke down. An American naval officer ran a Panamanian Defense Forces roadblock and was shot and killed. American soldiers commented that if a Panamanian were to run a US Army roadblock, they would open fire too.

Noriega then declared war against the United States. Never mind this declaration was mere hyperbole, a political speech. But when Noriega slammed a ceremonial sword on a lectern while giving the speech, the United States took him seriously.

On the evening of December 19th, 1989, despite the Panama Canal Neutrality Treaty, despite the assurances repeated by Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan, despite the official policy of the United States not to intervene in Panamanian affairs, the United States invaded Panama, removed Noriega from power and installed Guillermo Endara as the the new Panamanian president.

My client was arrested by the US Army in Panama and flown to Miami on New Year’s Eve. There he was met by US Attorney Dexter Lehtinen, who left a party though a few drinks in, who had been told that he would beet General Noriega. But Noriega was not on the plane, he had been given asylum in the Vatican Embassy.

The pilot’s bond hearing was scheduled for the morning of January 11th, 1990. I thought the hearing would be a formality. No one had ever been arrested overseas by US forces, flown back to the country and freed on bond. It had never happened. The whole world was watching.

One of those watching was Donald Mark Schoff, released early because of jail overcrowding and for good behavior. But Schoff was sill bitter. He believed he had been wrongly convicted.

Schoff’s solution was to seek revenge. He hired a cellmate to kill me. The amount agreed on was five thousand dollars. My life was worth $5000, just a little more then the real value of the washing machines and the refrigerators he stole or planned to steal, dragging what they couldn’t carry off to the doors of the apartments to be carried away,

Schoff knew that I lived in Miami, but didn’t know where. His cellmate had my office under surveillance for a week. He tried to follow me home several times but lost me in Miami traffic. Finally, one day when traffic was light, he was able to follow me all the way to my house off 17th Avenue in Coconut Grove.

At seven in the morning the cellmate parked his car behind the Shell station at the intersection of US 1 and 17th Avenue and crossed US 1. He walked to my house and hid in the bushes. A little after eight AM, I came out of the house carrying a cell phone and a folder of pleadings, marked United States v. Noriega. The pilot’s hearing was at 10 AM; there was plenty of time to get to the courthouse.

As I turned to lock the door, the cellmate yelled like an animal and came out of his hiding place in the bushes. Over his face there was a nylon stocking; in his hand was a hammer. He struck me in the back of the head. I turned, dropped the phone and the files and picked up a five gallon glass water bottle to shield myself. There was nothing else around the door.

A Panamanian single yellow head parrot lived in my house. In the jungle, a parrot’s screeches can be heard for up to three miles. Hearing the commotion, the parrot called loudly for other parrots to come and help.

Schoff’s cellmate was already running back towards US 1. In the mornings, the street in front of my house was used as a short-cut to avoid the long traffic light at 17th Avenue. A State policeman saw a man with a stocking mask running while holding a hammer. He gave chase and caught up with Schoff’s cellmate at the Shell station.

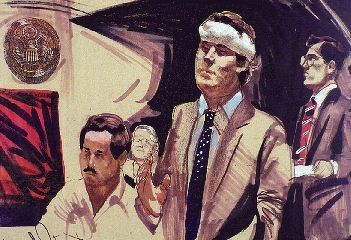

The ambulance came quickly. Rescue put a bandage around my head. They wanted to take me to the hospital, but I had to get to court. An NBC News5 reporter, Katrina Daniel, was also in the habit of taking the short-cut. She saw the ambulance and a man who looked like he was wearing a turban – me. She stopped and got the story.

When I arrived at the Miami federal courthouse it was a press scrum. Dozens of reporters wanted to know about this murder attempt and how it was related to the Noriega case. Daniel had seen the Noriega papers on the ground. The press had been alerted.

Magistrate Judge Peter Palermo heard what had happened and asked if I were able to go forward with the hearing. I told him that I was. After hearing arguments, Judge Palermo admitted the pilot to bond, an unheard of result. No one in the history of the American criminal justice system had ever been arrested overseas by the U.S. Army, dragged back for trial only to be freed on bond. I can only imagine that Judge Palermo felt sorry for me.

After the hearing I went to the hospital. I had suffered a concussion. The next day I got a phone call from the Broward Sheriff’s Office. They wanted to use Donald Mark Schoff as an informant. In the view of the detectives, the amount Schoff had paid his cellmate to kill me wasn’t enough for a murder. Maybe enough for a beating. But not a murder. Schoff was wired in and knew people the Sheriff’s Office was targeting. Did I have any objections?

“Go ahead,” I told them.

(Aftermath)

I never heard anything after that from the Broward Sheriff’s about Donald Mark Schoff, but I didn’t expect to either.

General Noriega went to trial. One of his attorneys, Raymond Takiff, turned out to be an informant for the US government. Takiff crossed his heart and said he never told the government anything he learned while representing the General. The judge believed him. Not everyone did.

Another of his attorneys, Neil Sonnett, resigned. General Noriega went to trial with Frank Rubino and Jon May, who gave him a competent drug defense case. I believe this was a mistake.

Napoleon felt that the defense strategy in the trial of Louis XVI was also an error. Noriega should have rejected the jurisdiction of the court, said that he was authorized to make any arrangements with traffickers that were in the best interests of Panama and Panama alone. After all, US government agents buy and sell drugs every day. Does this privilege not extend to the drug enforcement agents of another country? Similarly, Louis should have rejected the power of the court to sit in judgment of him, a sovereign.

The morning of Noriega’s trial, my pilot client pled guilty to a favorable plea bargain that allowed him to keep his FAA pilot’s license. He agreed to be deported to Panama. So there was to be no role for me at trial. The General was convicted and sentenced to 20 years in prison. All during that time, Noriega was technically a prisoner of war under the Geneva Convention. Noriega was allowed to wear a military uniform showing his general’s rank and was confined to a special housing unit built especially for him at MCC-Miami. A U.S. Army flag officer visited monthly to check on his welfare.

After completing his sentence, Noriega was extradited to France where he lost his military privileges. After a few years there, he was extradited back to Panama. He was never free and died while Panamanian proceedings continued against him.

I have no special insights about having suffered a crime. People connected the Schoff attack with the Noriega trial when there was no connection. A few days after the attack, one of my other clients had a pistol delivered to my home. A man I did not know rang the doorbell, asked my name, and handed me a paper bag and left. I was later asked later if I had received the package. The other client felt that I needed a gun to protect myself.

Surviving assassination attempts and the proper etiquette to be followed when receiving a pistol at your home were topics never covered in law school.

Years later, I discussed these events with an associate of New York’s Bonanno crime family. His view was cold:

“What are you complaining about? You’re here.”

Twenty-four years after he tried to kill me, Schoff’s sister shot him in the head and buried him in the backyard of her house in Dana Beach, Florida. Schoff’s body lay hidden for seven years until police received an anonymous tip. When they searched, their cadaver-sniffing dogs alerted to human remains.

Karma had finally come calling for Donald Mark Schoff.