UPDATED—October 31, 2025

An article in The American Scholar recounts the genesis of Jack Kerouac’s novel, On the Road. (https://theamericanscholar.org/scrolling-through/)

Tsk, tsk: the author fails to mention the long-lost—but recently found—Joan Anderson letter, written by Neal Casady. Kerouac himself attributed Casady’s style in the letter to helping him find a style appropriate to Road.

The Associated Press reported in late 2014 that a letter written by Neal Casady to Jack Kerouac in the 1950’s had been found after having been lost for sixty years. The letter is significant because Kerouac claimed that it was the inspiration that caused him to change his writing style, resulting in the best-selling novel On the Road. In his search In his search for a style appropriate to the tale of cross-country road trips across these United States, Kerouac had even written an early versions of On the Road in French, Kerouac’s first language. The voice of Kerouac’s first novel, The Town and the City was conventional, nothing like On the Road, which was written on a teletype roll so that Kerouac would not have to stop to change the paper in his typewriter.

In the 1940’s, while visiting New York, Casady spent a memorable weekend with a woman named Joan Anderson. Afterwards, he wrote a novella-length letter to Kerouac detailing the experience. Kerouac thought the letter was worthy of publication on its own, and so gave the letter to Allen Ginsberg in an effort to get the letter published. Ginsberg had acted as an unofficial literary agent for the Beats before. In the biography Jack’s Book, by Lawrence Lee, Ginsberg is quoted as saying, “I circulated all that material to the Partisan Review, brought a lot of it to John Hal Wheelock at Scribner’s, and talked to John Hollander, as an agent…” There is little doubt that Ginsberg was indeed acting as a literary agent, as claimed by the Casady Estate. Did Kerouac have Casady’s permission to submit the letter? Ginsberg knew Gerd Stern, whom he had met in a mental hospital where both were patients. Gerd had worked for a publisher and had contacts in the publishing world. Someone—Stern? Ginsberg? sent the letter to a small press in San Francisco called the Golden Goose Press. From there the trail went cold.

Ginsberg claimed that Stern, who lived on a houseboat, had dropped the letter into the ocean. Would the recovery of the letter necessitate an action for salvage brought under admiralty jurisdiction? Stern, who is the only living witness to these events, said that Ginsberg had lied. The truth was that the letter had indeed been received by the publisher. At this point it is not clear whether or not Golden Goose attempted to return the letter. When the letter was displayed recently in San Francisco at the Beat Museum, it was accompanied by a Golden Goose envelope. But it is unclear whether the letter was put into this envelope later for return to Stern or Ginsberg.

Later, the Golden Goose went out of business. Jack Spinosa, an accountant, had an office on the same floor in the building. When Golden Goose closed down, their trash was put out for collection. Jack Spinosa asked–or so it is said–if he could go through the trash. He did so, and took home papers which the Golden Goose had discarded.

Fast forward sixty years.

Jack Spinosa died and his daughter, Jean, came to clean out her father’s house. Amongst her father’s files, she found an envelope containing the Joan Anderson letter. (Note to the Associated Press: this was not the Golden Goose archive but material rescued from the trash.) The letter was in a Golden Goose envelope. Whom was it addressed to? Stern? Kerouac? Casady? Was proper postage affixed to the letter? It is not clear who had sent the letter to the publisher. Was it Ginsberg? Or did Ginsberg give it to Stern to send? When Ginsberg sent the letter to Golden Goose, he was acting as agent for Casady—through Kerouac—and was a bailee of the physical letter. Title to the letter never passed out of Kerouac’s hands unless Kerouac gave it or sold it to Ginsberg. Neither scenario is likely. Kerouac complained in a Paris Review interview that the letter belonged to him and that Ginsberg should have taken better care of it. This suggests that Ginsberg was a bailee—as literary agent)—or merely the agent of his principal, Kerouac.

When the letter was found, was it a letter or a manuscript?

Kerouac did not own all the rights to the letter. Under copyright law, the right to publish is distinct from ownership of the paper the letter is written on. Thus, the contents of the letter is the property of the Casady estate. The right of publication is thus held by Casady’s heirs.

An argument could even be made that Mexican law would apply because Casady died in Mexico. Was he domiciled there? Was Casady domiciled anywhere? His life was famously nomadic. Property that is owned by a person who dies without heirs is escheated to the state of the deceased’s domicile. But States in the United States cannot hold copyright, at least in the 11th Circuit.

The right to control publication of the contents of a letter is separate from ownership of the physical sheets of paper. James Joyce’s heirs prevented scholars from publishing his letters for years. A biographer who used J.D. Salinger’s letters to Joyce Maynard was forced to redact those letters from the biography. Salinger’s physical letters were put up for auction because they belonged to Joyce Maynard. They were purchased by Peter Norton (of Norton Utilities fame) who then returned them to Salinger. So while Salinger controlled publication of his own letters, he did not control the physical sheets of paper.

Glenn Greenwald of The Intercept complained when a lawyer sent him a threatening legal notice in the form of a letter and then claimed that copyright law prevented Greenwald from publishing the contents of the notice. A legal notice is not, however, a “work” protected by copyright law: Greenwald is free to publish the notice. Framing a legal notice in the form of a letter does not change this analysis.

A writer who submits a manuscript to a publisher does not surrender ownership of that manuscript to the publishing company absent a specific agreement to the contrary. It is a classic “offer to make an offer.” The fact that the Joan Anderson letter (or Casady manuscript) was found in Jean Spinosa’s father’s belongings does not divest the Kerouac estate of the right of publication. Does the passage of time affect ownership claims? In real estate, it certainly does: this is what is known as adverse possession. No similar rule exists in respect of copyright. Thanks to Sonny Bono and the Disney Company, the letter (or manuscript’s) contents are still subject to copyright. The Kerouac estate controls these rights–or does it?

The history of the Kerouac estate is convoluted. In litigation brought by Jack Kerouac’s daughter Jan, an appellate court in Florida ruled that the Kerouac estate exercises authority under a forged will. The Florida appellate court decision must be given full faith and credit in California. An objective observer might well conclude that Kerouac’s now-deceased daughter Jan was defrauded through the creation of a fraudulent will by Jack Kerouac’s wife Stella, and after her death, by Stella’s family. It is not clear whether the Joan Anderson letter is covered by the terms of the decision denying Jan Kerouac’s claim. But a court of equity will rarely give the benefit of the doubt to someone who inherited property under a forged instrument.

Not surprisingly, litigation has commenced. The Kerouac estate sued for possession of the letter. Jean Spinosa filed an action to quiet title. Casady’s heirs have made their own claim that not only are they entitled to control publication of the letter’s contents, but that the letter was a manuscript and so is their property. The dispute is not merely a theoretical one: the manuscript to On the Road sold for 2.4 million dollars in 2005. The physical pages of the Joan Anderson letter are expected to bring in at least a six-figure amount at auction. Publication rights are not included.

The Kerouac estate says once a letter, always a letter, claiming that the letter did not lose its character as a letter because Stern, Ginsberg and the Golden Goose may have treated the pages as a manuscript. But is this correct? Does a letter cease being a letter when submitted as a manuscript to a publisher? There was no copy made of the letter. The submission consisted of the original sheets of paper typed by Casey and mailed to his friend Jack.

And what of Jean Spinosa, the person who found the letter? She has rights to the letter under California’s abandoned property law—which is why the issue of the envelope and the existence of postage may be important. If Jack Spinosa removed the letter from Golden Goose’s outgoing mail rather than the trash, then he did not obtain possession legally. Otherwise, Joan may well have acquired title to the physical pages under California law.

Thanks to the Drug Enforcement Administration, Alan Weberman (the semi-famous Dylanologist, known for picking through Bob Dylan’s garbage) and many others (the Peruvian police were able to locate Sendero Luminoso’s leader, Abímael Guzmán, by looking through the trash) it is well established that there are no privacy rights to material thrown out in the trash and a person who picks an item out of the trash acquires title to that property. This is somewhat of a simplification–a person does not obtain a license to computer software by retrieving disks thrown out in the trash. At least, not yet.

Cases like this one are not likely to be seen again: people just don’t write letters like this anymore. Because a letter sent by email is not tangible, there is no bifurcation between ownership and publication rights. This distinction is almost as old as copyright law itself. Is losing the distinction important? ( I was wrong on this point, as the Greenwald example illustrates. The distinction may be with us for a while yet, especially if the lawyer who sent the threatening notice tries to sue Greenwald for a copyright violation.)

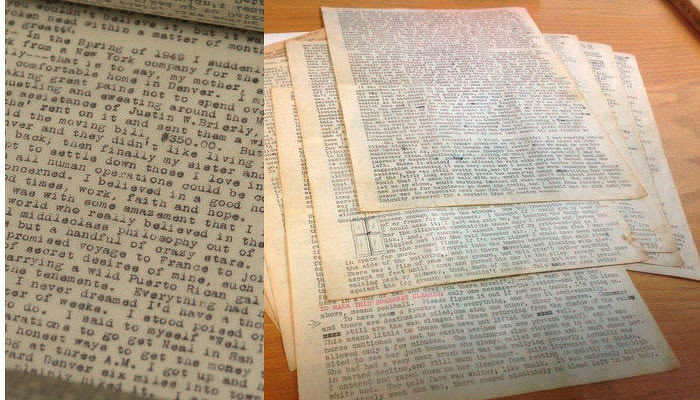

Portions of the letter have been published on the Internet. The photograph above shows the similarities between the physical manuscript of On the Road and the Joan Anderson letter.

Litigation over ownership to the physical letter was wisely settled by the parties. If news reports are correct, the judge in the case pointed out that it was in everyone’s best interests to come to an amicable agreement. This is what happens when someone with a strong case—say, the Kerouac estate—is made to realize that their position isn’t as strong as they had previously thought—such as when a Florida appellate court has deemed a will fraudulent. (Fraudulent will or not, I think it is fair to point out that the Kerouac Estate has done a good job of conserving Kerouac’s legacy and has fairly permitted access to materials, unlike the estate of James Joyce, which destroyed material.)

An initial effort to auction the letter by Sotheby’s failed as no bidder met the reserve. A second effort, conducted by a second auction house, resulted in the sale of the letter to Emory University in Atlanta. (news.emory.edu/stories/2…_kerouac_anderson_letter_acquisition/campus.html)

Unfortunately, the letter has not yet been published and litigation sadly continues. Perhaps the judge will use his powers of persuasion again so that we can all read Casady’s manuscript. Or letter, depending on your point of view.