Voltage in Saudi Arabia

Lately, I have had little success with cooking in Riyadh. My appliances, an air fryer and a coffee maker, simply did not work. A few days ago, I did find out, though at the moment I’m lacking instrument confirmation, why my appliances have not been working here. The air fryer’s fan did not turn. The now-boxed coffee maker took forever to bring water to a boil. I knew the three-pronged British-style outlet was working because the “on” light lit up on the coffee maker. I plugged another appliance in and it too, showed signs of life. So I went and bought a new coffee maker. No sooner had I freed the machine from its box that it exhibited the same symptoms: the power light illuminated but there was no hot water. In my mind I ran through taking the coffee machine back to the store, the drive through horrible Saudi traffic, language difficulties, a test at the store to insure I am not a scam artist of some kind. I had already been through this recently after I replaced the air fryer.

But then, something happened. I don’t know why I did this, but I plugged the new coffee maker into another outlet on the other side of the kitchen. Not only did the power button illuminate, but the machine steamed, gurgled and started spitting out hot water. We’ll leave a discussion of this inspiration or message from the Gods for later, but as water dripped into the basket holding the grounds I realized what had happened and I felt like a fool: if anyone should have been able to diagnose the problem, it should have been me. But I failed.

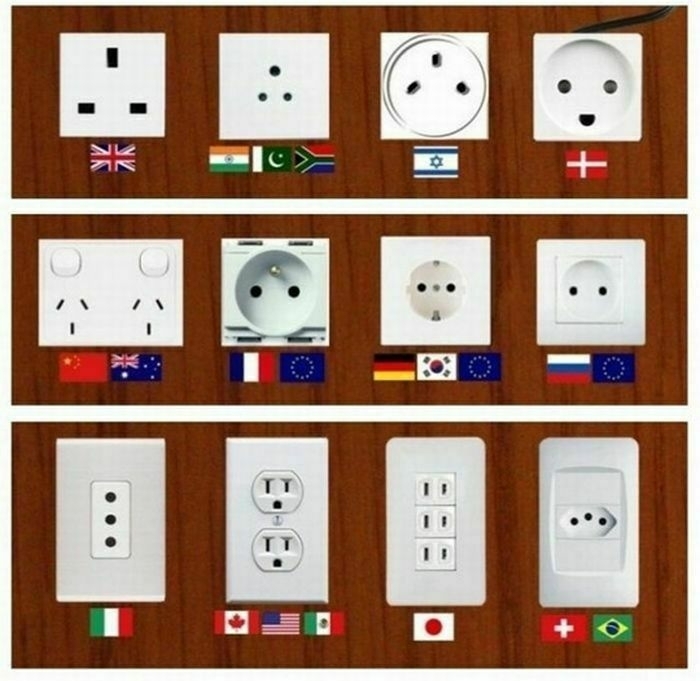

When I came to Saudi Arabia, you couldn’t trust electricity. A home might have round European outlets; flat American ones or three-pronged British ones. If the builders ran out or a previous tenant had made a change, you might find slanted Australian plugs or even the thick tusks of a South African plug. In some cases, tenants simply removed the plug, stripped the wires and inserted bare wires into the outlet, ignoring the preferred plug. In any event adapters were easy to find and were sold in all the grocery stores. There were times when I was back in the US or in Europe and realized I needed an adapter. “I’ll just get one when I get back to Saudi” was my solution.

What voltage the outlet supplied was a matter of guesswork. You certainly couldn’t determine the voltage by looking at the outlet. The energy supplied might be 110v, 220v, 100v or—in the laundry room—440v. One of the first things you had to do was acquire a voltage meter. The meter would tell you what was coming out of the outlet. The next step was to write, in black marker, the results on the white outlet. The outlets are always white. There’s a market for a canny home designer who can bring out a line of colored outlets. But I digress.

About five years ago, or maybe a bit more, one of the Saudi ministries (I can think of several that might have had a hand in this) decided to standardize on British plugs. With each plug containing its own fuse, these are the safest. They also decided on 220v, to at least standardize with the UK and with the added benefit of conformity with the United Arab Emirates, Oman, Bahrain and I think Qatar. There is an international agency called the “GCC Interconnection Authority” that was attacked by Al Qaeda around 2002 or so and that agency might have weighed in on the subject. While 110v is normally insufficient to kill a man, 220v packs a sufficient punch. Safety often carries trade-offs of one kind or another.

Prior to standardization, I bought a microwave manufactured in China that carried a round European plug. Despite the European plug, the device ran on 110v. Perhaps the factory ran out of flat plugs on the assembly line, knowing that the fault would be overlooked in Saudi Arabia. Fortunately I read the manual before blowing up a bag of popcorn.

On one occasion, I left Riyadh on extended leave and left the microwave in my apartment. The white outlets were clearly marked. While I was gone, my employer let another attorney use the apartment. Excited by the prospect of tasty popcorn, and not bothering to read the manual, the new tenant looked at the round European plug and was not so provincial as to lack knowledge of its meaning, but not cosmopolitan enough to realize that in Saudi Arabia, making assumptions carries risks. He plugged the microwave into the appropriate outlet. Two hundred and twenty volts surged through the machine, twice the amount that the machine was designed for, and laid it to rest.

“Sorry about your microwave. I don’t know what happened,” was the mea culpa in the note he left me. But I immediately knew what had happened. You can plug a 220v device into a 110v outlet and it will sputter but it will not be ruined. Plug a 110v appliance into a 220v line and there will be a bang, perhaps a flash and that acrid smell often accompanied by the kind of smoke that sets off fire alarms, leaving the appliance ruined.

It is one thing to have an international agency advise the Saudi Ministry of Housing and Rural Affairs (MoMRA), the Ministry of Electricity and the Ministry of Interior on standardization in the field of the supply of electricity, followed by an amendment to the Saudi building code. It is quite another to have this new rule explained to someone wearing a tool belt who has just arrived from Bangladesh and whose main concern is sending money to his poor family back home.

The assignment would be given in English—not the native language of the foreman—to the newly-minted electricians whose native language wasn’t English either. If they want all the outlets to conform to the British standard, that’s what they’ll get. The tool belt guy would turn the power off at the source and replace the offending outlets with the correct ones. Then he would turn the power back on and throw the old outlets into the bin. Then, on to the next.

No one would come by afterwards and mark the outlet. There was no need because the tool guy had already changed the outlet and marked it on his checklist as conforming.

So that’s what happened. Silly me. I plugged a perfectly good, 220v coffee maker into a 110v outlet. No matter that the plugs matched, there wasn’t enough voltage to reliably heat the water. The 220v volt air fryer also malfunctioned, there was barely enough power to warm the heating element and not enough to get the blades of the fan to turn.

In short, I should have known better. In my defense, I’m not the only one who has made this mistake. Pre-pandemic, there was great concern in Saudi hospitals about the sterilization of hospital rooms where avian influenza victims have been treated. Muslims from all over the world come to Mecca to pray and they bring their diseases with them. An American medical devices salesman had the solution to this problem: a robotic machine that sterilized a hospital room using ultra-violet light. He proposed to sell the robotic sterilization device to the Ministry of Health. Before committing, they asked for a demonstration to be conducted in Riyadh. The salesman made hurried arrangements to have the device air-freighted to King Khalid airport. It arrived in just three days. Various Saudi officials, including the Minister of Health himself, attended the demonstration. The salesman whipped through his presentation and then…plugged the machine into the wall.

The Minister of Health was not the only one who heard a loud “pop” before the fire alarm went off. The Kingdom declined to enter into further contract negotiations.

I could buy a voltmeter—these days they’re hard to find— and test the rogue outlet, but why? I am reasonably sure that the digital display will read ‘110’ and not ‘220’ and I don’t have any 220 appliances here anyway. Importing them is technically prohibited. I say “technically” because Saudi Aramco, the country’s oil company, has historically supplied 110v to its compound in Dhahran. There is a Royal Decree which says that Aramco is privileged to ignore Saudi laws when they conflict with (and could possibly harm) Aramco’s operations. So Aramco can import appliances that otherwise would be confiscated. So if you are going to Dhahran, you better get yourself a voltmeter.

You never know what’s behind the wall.