The predilection for writing letters did not begin in Bahrain. In another lifetime, I worked for the Panama Canal. One of the benefits, at least as seen by one who suffers the affliction of writing letters, was a provision of the Panama Canal Treaty which gave employees of the Canal access to the military postal system until the end of the so-called “transition period,” which began on the treaty’s effective date of October 1, 1979 and ended on April 30, 1982.

The incidents of sovereignty were slowly being cast off, and like Y2K (though no one had heard of that then, obviously) no one was really sure if all the bases had been covered in the treaty, the implementing agreement, the newly renamed Canal Zone Code and any other regulations, instructions or memoranda that were flitting about. Taking down a flag is easy, but not everything else that needs to abolish a jurisdiction is so simple—e.g., they retained limited criminal jurisdiction but forgot to provide for federal public defenders. Typical.

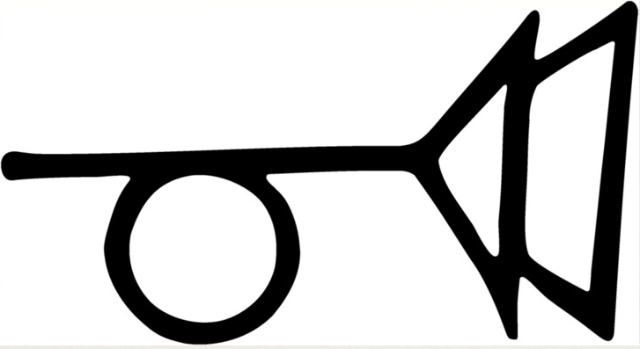

In those days, the idea of privatizing a national post office was unheard of. The flag followed mail carriers as they made their rounds, historically it was one of the few federal institutions that touched people’s lives (at least until the income tax became law) and stamps were as good as currency. The Canal Zone had its own post office. When, on October 1, 1979 they took down the flag, that post office went out of business and was turned over to the Republic of Panama’s own postal system.

So, for thirty-one months, Panama Canal US citizen employees had access to the military postal system. The idea, I suppose, was that this would cause as little impact as possible on those who wrote letters, read magazines or received Jenny Craig diet products through the mail. Sending letters overseas in those days was complicated; half the time the postal clerk would have to pull a black binder from a shelf in someone’s office to check if there were any special mailing requirements. During the Canal Zone days, mail from the US was domestic; similarly, mail that traveled through the military postal system was also considered domestic for the most part. You had an APO (Army Post Office) address in Miami and were charged parcel rates to Florida.

I quickly read the writing on the wall and knew that I, along with about 1700 others, would soon lose military mail. This was disconcerting. I sent a questionnaire around to military post offices in different countries to see how they handled things and if there was any regulatory holes into which we might, in the future, place letters.

Civilian US employees in Korea were unionized and active; perhaps they had figured something out. We were theoretically a part of the Department of Defense, after all, but just barely. The fight over the Canal Zone was in the past and the focus was now on obtaining Panamanian support, or at least no-objection, for our backing the Contras in Nicaragua, not to mention the FMLN unpleasantness in El Salvador.

The Gipper took to the airwaves and showed the public how close Nicaragua was to Texas; communists could any day now be at our shores. Cuba was closer, of course, but that conflict had long been back-burnered.

I obtained no results and no hope from what the Pentagon called my “unauthorized world-wide survey” of military post offices. I thought they were being a little dramatic. April 30, 1982 was rapidly approaching and with it, the likelihood of weight gain if Jenny Craig’s tasty meals became uneconomical due to an increase in postal rates.

What then, to do? I was completely out of ideas and could only dread the inevitable. That day in April finally came and with it, an extraordinarily rare ceremony was held, the closing of a United States District Court. As far as I know, only two US district courts have ever closed. The US District Court for China was closed when the Japanese invaded Shanghai in WWII, and the US District Court for the Philippines was closed when the Imperial Japanese Army displaced General MacArthur. Neither court was ever to open again.

No violence attended the closing of the Canal Zone court. The ceremony was presided over by the Fifth Circuit’s chief judge, Charles Clark. The general staff of the Panamanian Defense Forces filled up the jury box. Judge Morey Sear, the last Canal Zone district judge, sat next to Judge Clark.

My boss, Dwight McKabney, later wanted to prosecute Judge Sear for “donating” a bench from the court to Tulane Law School. McKabney felt this was an unauthorized transfer of government property. His own boss wanted only for Canal affairs to be run smoothly. Making an accusation against a federal district judge with life tenure was not, in his view, a good idea. With the end of the transition period Sear lost his diplomatic passport and sinecure in the Canal Zone. But he was still a sitting judge in New Orleans of the District Court of the Eastern District of Louisiana, where I used to spend time in Tulane’s library while preparing for the Louisiana bar exam. No accusation was ever made against Sear. In 1987, the bench was still in Tulane’s law library and as far as I know, remains there today.

On that April day I met Colonel Manuel Noriega for the first time. He was our ally then. General Torrijos had died in a plane crash less than a year before and the military general staff were still jockeying for position. I shook his hand but didn’t have any conversation other than perhaps exchanging mutual “mucho gustos.” The Canal had good relations with the Colonel, who at that time was powerful but not formally in a leadership position. The Canal had a special liaison office with the Panamanian Defense Forces and things ran smoothly, at least until we decided to ignore the treaty and invade Panama eight years later—a treaty violation, I’d like to point out.

On the day after the ceremony, there was no more mail. Everyone’s post office box—for there never was door to door mail service in either Panama or the Canal Zone—was closed.

Or was it? For some strange reason, and clearly a violation of the blessed treaty reached by two sovereign nations—my box continued to receive mail. It was just a regular post office box—PSC (Postal Service Center) Box 843, APO Miami 34002. Against all odds, somehow my box had remained open at Albrook Field.

I felt like a criminal when I went to pick up my mail. I wasn’t supposed to be there. If they asked for the military ID which authorized me to pick up mail, I had nothing to show. It is hard to act surreptitiously in a large post office with circular mirrors where the walls meet the ceiling bathed with white light from the batteries of fluorescent tubes illuminating postal customers from above. For a month or so, I pretended like I had a right to be there, found my box and turned the combination knob. Twice to the right, once to the left and the box opened.

But one day the combination stopped working. The box wouldn’t open. There was no mail for me. I went to the former Canal Zone post office in Balboa. For a little more than two years it had been an unused outpost of the Panamanian postal system. I signed up for a box and was assigned Box 2914; but I had to call the box “Apartado” because English was no longer allowed. Day followed day without mail.

In these days of instant communication, e.g., “I texted you five minutes ago. Why haven’t you answered?” and free international voice calls (WhatsApp, Line) the isolation that separated people at a distance is forgotten. But it was isolation and that distance caused friendships to be lost. When someone left town they were, in effect, gone for good, unless they returned. This effect was magnified when anyone left for overseas. Mail was one way to breach the distance and stay in touch.

Though it had nothing to do with the unauthorized survey, by pure coincidence I found out that US citizens in Haiti had access to the State Department diplomatic pouch to send and receive mail. The privilege was restricted to government employees working in Haiti. There was an alternative mail system after all.

I didn’t see any reason why this couldn’t work in Panama. The effect of the Treaty was to deprive US citizen PanCanal employees of their access to the mails as a consequence of the disestablishment of the Canal Zone. Without a political entity, there could be no post office. The mail was an incidence of sovereignty and a vestige of a now-objectionable colonial period. Soldiers might get US mail, but civilians? Unthinkable.

The concept of privatizing government assets had not yet reached the Western democracies. Instead, the pendulum swung the other way: “nationalization” was the way that governments took the assets of foreign companies, usually American companies at that. The American attitude was that this was just a few steps away from socialism or communism and must be resisted at all costs.

Privatization was not a word in anyone’s vocabulary. Had it been, the Canal Zone post office might have been sold to FedEx or DHL, except back then, the former didn’t exist and the latter was a messenger service that only delivered documents after-hours to attorneys in Northern California.

By the time US mail service was cut off I was living with a parrot that had developed a fondness for the maid’s daughter, Katia. The parrot cried out Katia’s name at all hours of the day and night. Jungle parrots can hear each other’s shrieks at a distance of three miles. My living room was not that big. The parrot’s loneliness was contagious. I was discouraged only when there was no mail in the apartado but when Katia wasn’t around the parrot was inconsolable.

I formally submitted the issue of access to the diplomatic pouch to Canal management and was told that access was not possible. When asked for the legal basis for this view, I was referred back to the treaty. But the request as framed had nothing to do with the treaty. All that was in the past. Diplomatic pouch access was in the present and was common in Haiti as well as other countries. Those who were telling me this didn’t realize that they had no legal basis to say ‘no’ because if they said ‘no’ they would be admitting that we really weren’t a federal agency or that we weren’t really federal employees and that they could not do.

Negotiations continued but eventually I got a call. They had set up a new post office for the employees through the embassy’s diplomatic pouch. It was more restrictive than the military postal system, but now those who watched their waistlines could get their Jenny Craig again. Thomas Pynchon wrote about a mysterious secret postal system called the trystero in his novel, The Crying of Lot 49. My trystero ran for almost two decades.

In Panama I lost my respect for the Rule of Law. When you can pick and choose which laws to obey and which ones to ignore, whether the subject of your legal inquiry is a wooden district court bench or a lonely parrot shrieking for a friend, you lose respect for the supposed black and white Rule of Law very quickly.