Whose Fault?

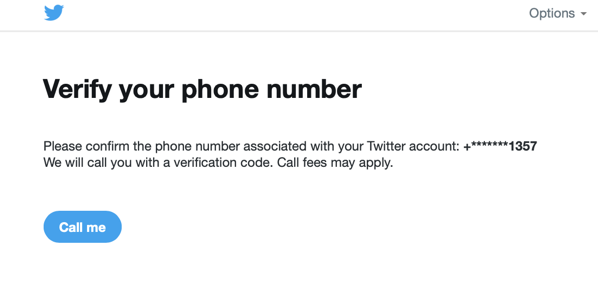

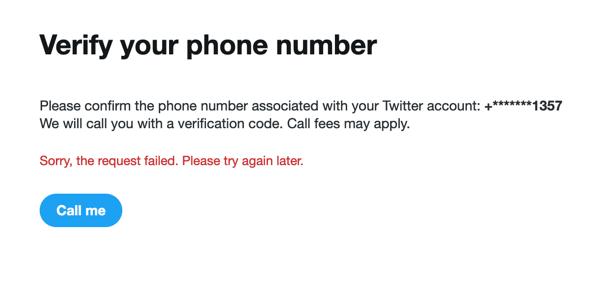

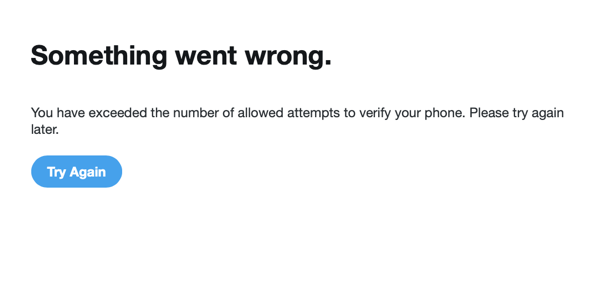

When I woke up one morning in June, there was a message from Twitter on my phone, telling me that there was suspicious activity on my account and that they would send an SMS code which I should then enter on the screen to be provided. I clicked “OK” or “Send.”

But no message arrived.

I clicked again. Nothing. And again. Nothing.

I opened Twitter on my laptop to find that my account had been suspended. I clicked on the blue box now prominently displayed at the bottom of the screen to “Find Out More.” A new window opened, with a form to fill out an inquiry. I filled out the form, pressed “Send” and got a new screen thanking me and saying that under normal circumstances, these issues are resolved in a day or two.

I received an email telling me that my inquiry had been received and registered and that Twitter would address the issue as soon as they were able.

Time Passes

A few days later, I had received no further message from Twitter and my account was still suspended. I sent a follow-up email which was instantly replied to noting that I had an open inquiry and that the new email would be added to the open inquiry. That was fine with me, so I waited.

And waited some more.

Now a week had gone by. Was I being de-platformed?

De-Platformed?

I do not know what algorithms Twitter uses to place posts in my feed. My standard rule is that if a post shows up in my feed, it is inviting a response. I may or may not respond if I have anything to add to the discussion. Sometimes I do, but usually I don’t.

The subject of de-platforming comes up frequently. There are basically four sides to this argument:

- de-platforming is censorship, violating the First Amendment

- de-platforming is not censorship, because Twitter is not the government and the First Amendment only addresses government action

- a particular person should be de-platformed because he violated Twitter’s ToS and community standards

- a particular person should not be platformed because de-platforming is in effect censorship or because their posts aren’t that bad or don’t violate Twitter’s community standards.

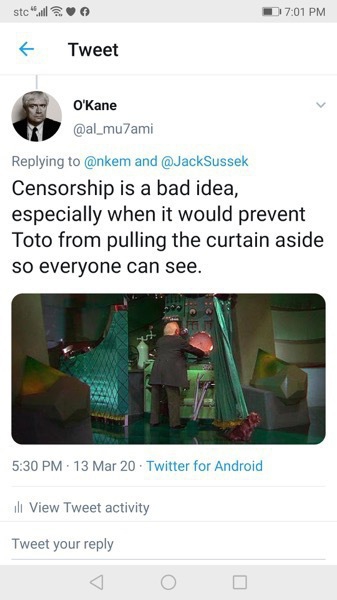

Proponents of any of these four arguments like to make them. My personal position is that Twitter is not a publisher and should not be a censor. The only ones who should be censored are those who call for censorship. Edge cases can be dealt with in the courts. My personal opinion is but one of millions and there is no reason to give it more credence than anyone else’s.

In my opinion, time has affected these arguments. Twitter is clearly a public place. The president uses it to communicate directly with the people. If the president can do so, so can any other public official. And so can anyone else who disagrees with that public official.

In my opinion, sometimes a platform can become “too big to censor.” Twitter is such a platform. A local chess club bulletin board with news of upcoming events and analysis of recent games is not. No one would argue that the chess club has a right to keep non-chess posts off its site. But Twitter and Facebook are in a different category simply because of their size and reach.

There is no legislation which would eliminate their claimed right to censor. Such legislation is needed to address the situation where a large public forum undertakes to censor information where, if the government were to take the same action, would be considered free speech. It’s not difficult to write such legislation: make the law applicable to platforms with a half million users or more. There’s an equal protection counter-argument here and there would be a great deal of legal squabbling before things settled down.

From time to time I would point out that the largest shareholder of Twitter, other than its founders, is (or was) Saudi Arabia’s Prince Walid bin Talal. I do not believe that Prince Walid ever tried to censor Twitter posts. Nevertheless, it would be difficult for Twitter management to resist an initiative by a major shareholder to ban those critical of Saudi Arabia, critical of Israel, or critical of any other country.

But I have few followers (probably less than one hundred) and I don’t think that either Jack Dorsey or Prince Walid himself feels especially threatened by my comments about de-platforming.

I hadn’t written anything praising Antifa, inciting armed insurrection, organizing militias or planning bombings. Other than pointing out that Senator Marco Rubio is a Mormon from Utah and not the Cuban refugee he pretends to be to his constituency in Florida, I hadn’t posted anything about religion. I have often criticized the FBI’s use of informants to trap the weak and have written about the Liberty City 7 case in Florida. It is highly unlikely that the FBI felt so threatened by me that they sought to have me censored.

I support the #DignidadLiteraria movement and posted complaints about the Irish-American fantasy novel #AmericanDirt, but if my comments about a Twitter shareholder didn’t merit corporate attention, neither did my posts about these topics. I have written a blog post about George Floyd and the teenagers who “thought” he might have paid with a counterfeit twenty after he left the store and another about Rayshard Brooks which pointed out that deadly force cannot be used to stop a misdemeanant, but both articles were too long for Twitter. I only linked to them. In short, I just wasn’t much of a controversial Twitter user.

So if I wasn’t de-platformed, what was going on?

Meanwhile, I sent another e-mail to Twitter and received the same automated response. No human being had yet reviewed my issue.

June became July and July became August.

Snowjob

The US Government waited until Carlos Lehder had terminal cancer before fulfilling its promise to permit his transfer to Germany. The promise was made to induce Lehder to cooperate in the prosecution of General Manuel Noriega of Panama. After invading Panama, that prosecution was one the US could not lose. Cooperation deals rained down like a burst piñata.

I wrote the introduction to a book entitled Snowjob, by Carlos Stier, one of Lehder’s erstwhile lieutenants. Lehder’s transfer was world news—news that showed up in my Twitter feed. Repeatedly, post after post, new posts and retweeted posts and commented upon posts. At least one hundred of them.

I commented on about twenty of these, posting this graphic.

Oops. Twitter thought I was a bot. That’s why they checked and sent the SMS inquiry. When Twitter’s bot thought that I was a bot, it responded by suspending my account. But I wasn’t a bot.

Another email to Twitter was followed by yet another automated response. I tried a new tactic and sent an email to Twitter support. I received a response noting that I had an open inquiry with Twitter and that my new support request would be joined with the open inquiry, an inquiry that, I decided, had determined I was a bot and that there was no need to respond.

For whatever it’s worth, I didn’t even post the same graphic each time.

In a way, I can’t blame Twitter. How many support personnel would you have to hire to deal with millions of users? The labor payroll would be a staggering expense. On the other hand, Google doesn’t seem to have any support personnel at all. There are stories of people losing their passwords and never getting their emails back. The only Google support team exists to sell you advertising. That team is happy to speak with you on the phone and will even try to schedule phone appointments with you that you haven’t asked for. Have you ever tried to get Google on the phone? The only department that takes calls is the legal department and that’s limited to law enforcement emergencies and…

…that gave me an idea. That was the way in.

I’m not law enforcement and I don’t have an emergency, but perhaps the best way to handle this issue was to move it from the cyber world to meatspace, a term I had not even seen for some time.

August became September; September became October.

USPS To the Rescue

I hooked up my occasionally used printer and printed out screenshots and emails. I then wrote a letter and addressed it to Twitter’s Security Department. I looked up the street address, which Twitter helpfully publishes, presumably to assist with law enforcement subpoenas.

I went to the post office where the envelope was stamped and accepted for delivery. I calculated that delivery would take a few days.

There’s Something About Paper

Jay Foonberg is an attorney and author of How to Start and Build a Law Practice, the book most-stolen from law libraries. In that book, he recommends sending clients a copy of all correspondence received and all correspondence sent. Any pleadings filed or received should be copied and mailed to the client. The reason for doing so is not immediately obvious, but there is a clear financial reason to do so: it is difficult for a client to claim “my attorney hasn’t done anything” while staring at a column of paper stacked to the ceiling.

“You have to do something with paper,” Foonberg instructs. “Even if it’s just a question of throwing the paper into the trash, someone has to physically take out the trash.” Paper sits on a desk or hides in a file cabinet taking up space. Until it’s dealt with, paper is an action item. When it sits on someone’s desk paper is a reminder of work not done, not put away, it is there for anyone—and especially a supervisor—to see. In short, paper cannot be ignored.

One week after I mailed my letter, one week after the move from the ethereal to the physical, my account was restored.